De scheepsschroef

De bulk van de handel gaat over de wereldzeeën. Dat is al eeuwen zo. Eerst per zeilschip en sinds de tweede helft van de negentiende eeuw gemotoriseerd. Met dank aan de uitvinding van de scheepsschroef. Maar wie kwam op dat idee?

Tekst: Rob van ’t Wel. Beeld: Getty Images

Scroll down or click here for the English version

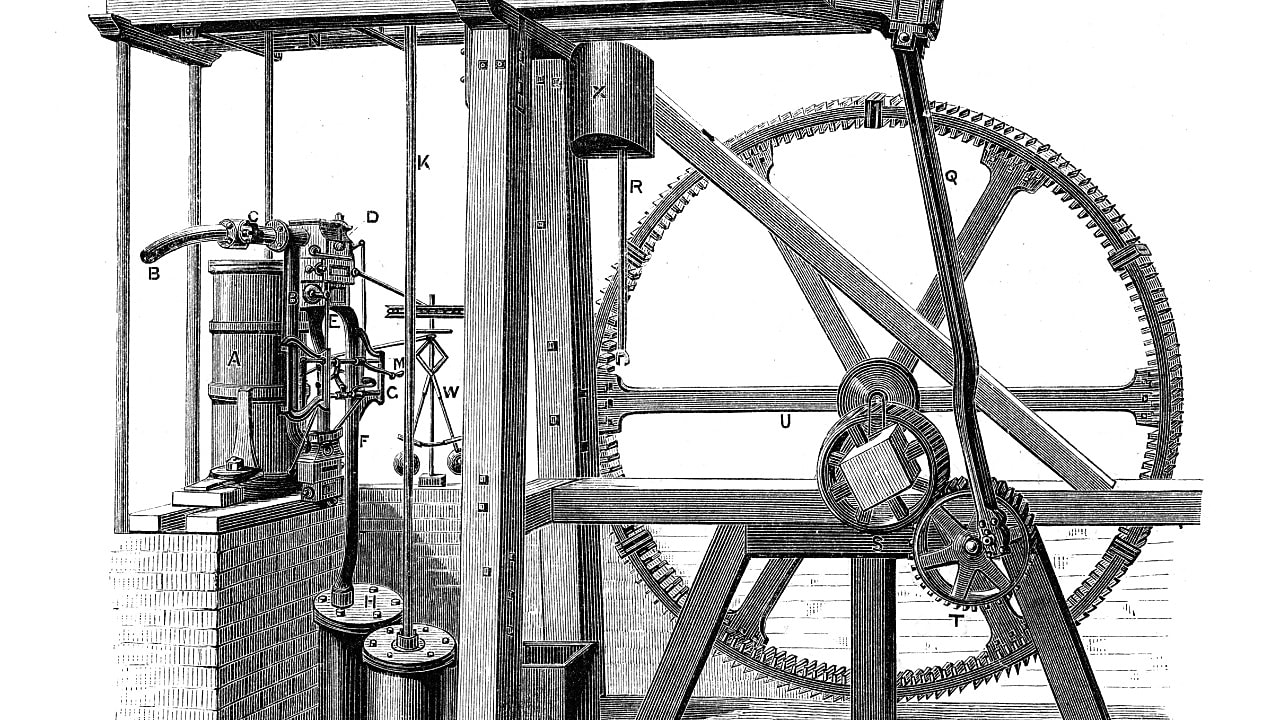

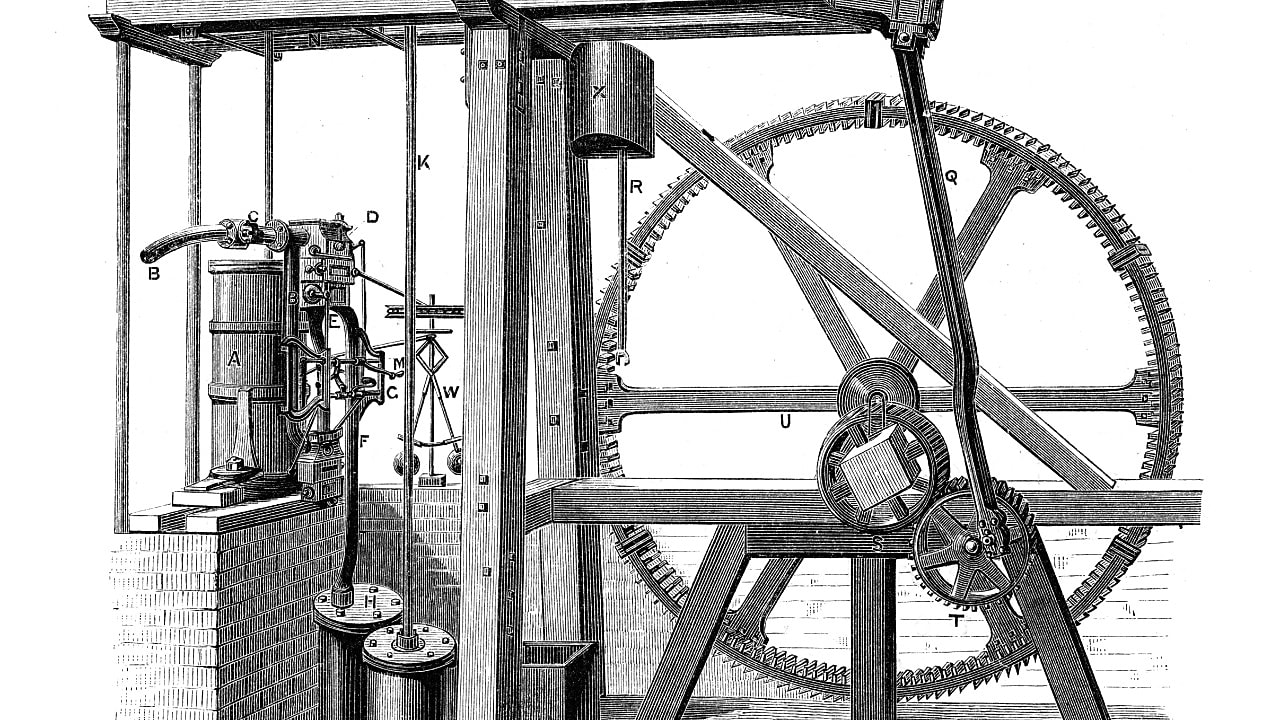

Zoals zo vaak kent succes vele vaders en in dit geval letterlijk. De oude Egyptenaren waren al aan het puzzelen. De Griekse wiskundige Archimedes gaf ook een klap op de ontwikkeling. En ook Leonardo da Vinci stoeide met het idee, al zette de Italiaanse alleskunner de schroef op iets wat we nu als een helikopter herkennen. De scheepsschroef zelf moest wachten tot de uitvinding van een bruikbare stoommachine. Hoe fijn zou het voor de handel niet zijn, als de onvoorspelbare zeilschepen vervangen zouden kunnen worden door een betrouwbare krachtbron in het ruim?

Toekomst zien in de raderboot

Dat vooruitzicht zet de technologische pioniers in de maritieme wereld aan het denken. Ze worstelen collectief met twee hoofdproblemen. De eerste is dat er in de scheepsromp een gat moet komen voor de door de stoommachine aangedreven as. Dat probleem blijkt overkomelijk. Het tweede probleem leidt tot een technologische tweestrijd. Aan de ene kant zijn er de uitvinders die brood en toekomst zien in de raderboot. Aan de andere kant zijn er de techneuten die veel meer zien in het vervolmaken van een idee waar al eeuwen mee wordt gespeeld: de schroef.

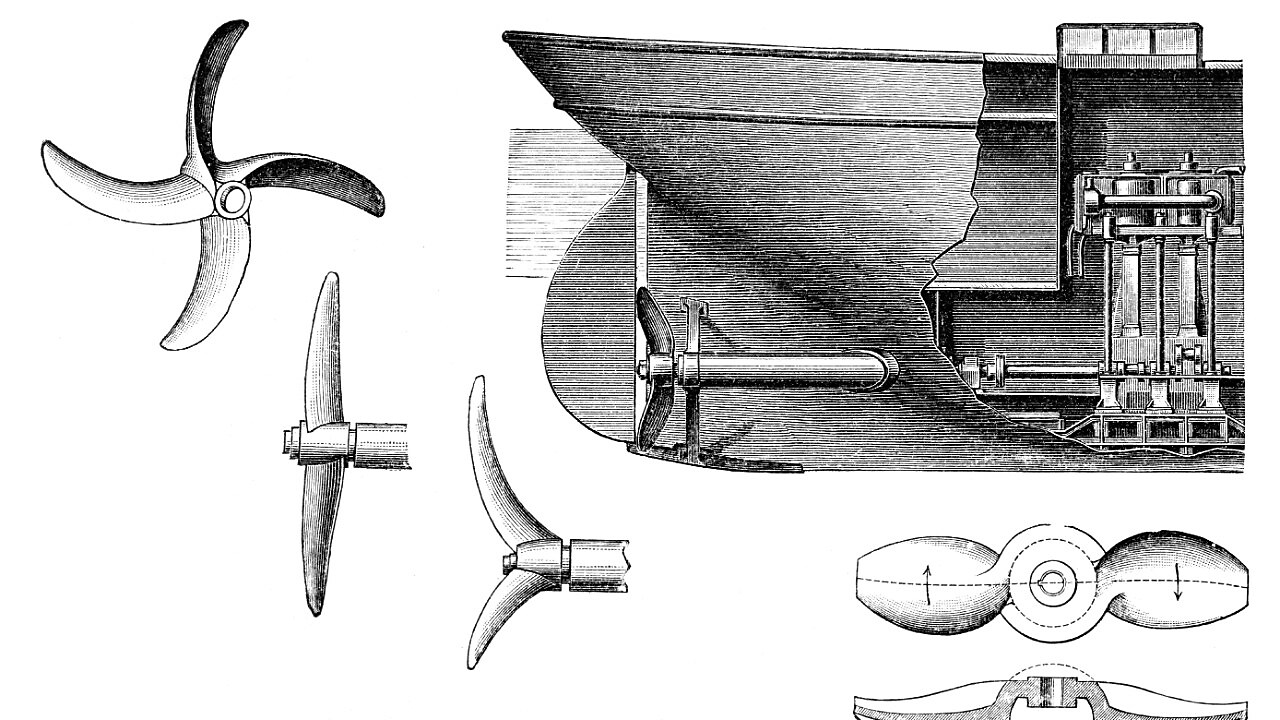

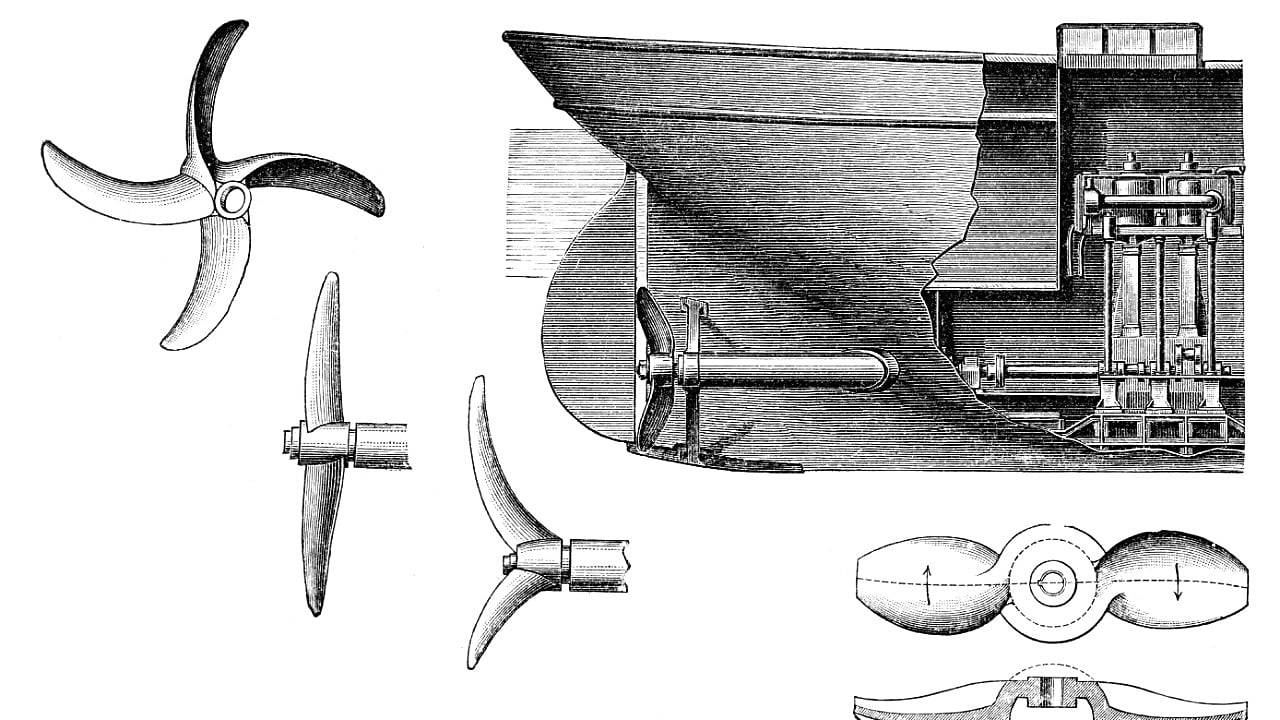

Die nieuwe vinding bestaat uit een naaf met daarop minimaal twee bladen, die symmetrisch onder een hoek zijn geplaatst. Bij het draaien ontstaat er dan een drukverschil tussen de voor- en achterzijde, zoals dat bijvoorbeeld ook gebeurt met de ouderwetse ventilator die ’s zomers thuis verkoeling biedt.

Vaders van de scheepsschroef

De gepatenteerde vaders van die scheepsschroef komen uit Oostenrijk, Engeland en Zweden: Josef Ressel, Francis Petit Smith en John Ericsson. Van dat drietal geldt Josef Ressel, een uit Bohemen afkomstige bosbouwambtenaar met voorliefde voor techniek, als de voorloper. Hij vraagt op 11 februari 1827 een octrooi aan op een aandrijfwiel waarmee schepen zich kunnen voorttrekken.

Oorlogsschip USS Princeton

De Brit Petit Smith doet negen jaar later hetzelfde na uitgebreide testen met een modelboot. Hij bouwt in 1839 met succes het eerste door een schroef aangedreven stoomschip, die niet toevallig de SS Archimedes wordt gedoopt. De via Engeland naar de Verenigde Staten geëmigreerde Zweed John Ericsson bouwt enkele jaren later het oorlogsschip USS Princeton. Dit is het eerste schip met twee tegen elkaar in draaiende schroeven. Geen enkel ander marineschip kan op dat moment tippen aan de snelheid van de USS Princeton. Sindsdien is de scheepsschroef dominant.

Uitschuifbare vleugels

Hoewel. Een groep Zweedse ingenieurs werkt aan een schip met vijf enorme uitschuifbare vleugels om ook gebruik te maken van de aloude wind. Op die manier zou de uitstoot met 90 procent kunnen worden teruggedrongen.

Lees ook in deze serie

"De scheepsschroef" is het tweede deel in een driedelige miniserie met het thema Bronnen van beweging. Het eerste en derde deel, "Paardenkracht" en "Peristaltiek" zijn ook online verschenen. De serie staat ook in Venster #1-2024.

Meer nieuws uit Shell Venster

Forces of movement - from a series of three stories published in Shell Venster Magazine #1-2024The ship's propeller

8 Feb. 2024

The bulk of the trade goes across the world's oceans. This has been the case for centuries. First by sailing ship and since the second half of the 19th century motorized. Thanks to the invention of the ship's propeller. But who came up with that idea?

Text: Rob van 't Wel. Illustration: Getty Images

As is so often the case, success has many fathers and in this case literally. The ancient Egyptians were already puzzling on a better propulsion. The Greek mathematician Archimedes was pushing for its development. And Leonardo da Vinci also toyed with the idea, although the Italian all-rounder put the screw on something we now recognize as a helicopter. The ship's propeller itself had to wait until the invention of a usable steam engine. Wouldn't it be nice for trade if the unpredictable sailing ships could be replaced by a reliable source of power in the hold? was the general question to be answered.

Future of the paddle steamer

The prospect occupies the brains of the technological pioneers in the maritime world. They collectively struggle with two main problems. The first is that there must be a hole in the ship's hull for the shaft driven by the steam engine. That seems feasible. The second problem leads to a technological dilemma. On the one hand, there are the inventors who see the potential and the future in the paddle steamer. On the other hand, there are the technicians who see much more in perfecting an idea that has been toyed with for centuries: the propeller.

This new invention consists of a hub with at least two blades on top, which are symmetrically placed at an angle. When running, there is a pressure difference between the front and rear, as is the case with the old-fashioned fan that provides cooling at home in the summer.

Fathers of the ship's propeller

The patented fathers of the ship's propeller come from Austria, England and Sweden: Josef Ressel, Francis Petit Smith and John Ericsson. Of these three, Josef Ressel, a forestry official from Bohemia with a penchant for technology, is considered the forerunner. On 11 February 1827, he applied for a patent for a drive wheel that could be used to pull ships.

Warship USS Princeton

Briton Petit Smith does the same nine years later after extensive testing with a model boat. In 1839 he successfully built the first propeller-driven steamship, which was not coincidentally christened the SS Archimedes. A few years later, the Swede John Ericsson, who had emigrated to the United States via England, built the warship USS Princeton. This is the first ship with two propellers rotating against each other. No other naval ship at that time could match the speed of the USS Princeton. Since then, the ship's propeller has been dominant.

Extendable wings

But with a footnote. A group of Swedish engineers is working on a ship with five huge extendable wings to make good use of the good old wind. If successful, emissions could be reduced by 90%.

Also in this series

"The ship's propeller" is the second publication in this miniseries themed around Forces of movement. The first and third parts, "Horsepower" and "Peristaltis", have been published as well. The series is also featured in Venster #1-2024.