Shell Biogas en de Nederlandse ambities: grootste in groen gas dankzij Deens boerenverstand

Stel, je hebt een boerenbedrijf. Het rogge en tarwe van jouw land gaat in het brood dat mensen voedt. Maar het blad en de stengels van het gewas, daar kun je niet zo veel mee. Zie daar Shell Biogas, sinds september de nieuwe naam van het van oorsprong Deense Nature Energy. In Denemarken heeft biogas een lange traditie. In Nederland wat minder, maar ook in ons land wil Shell de komende jaren verder groeien met deze aardgasvervanger.

Tekst: Marcel Burger, met een bijdrage over de Franse biogasfabriek van Molly Lynch.

Beeld: ANP/HH/Marcel Berendsen, Shell Biogas/Claus Haagensen, AdobeStock.

UPDATE 2 okt. 2025 in alinea Nature Energy sinds 1979 producent van biomethaan: Northstar in Emmen toegevoegd

De overname van Nature Energy door Shell werd in november 2022 aangekondigd. Nu ook de naam is gewijzigd in Shell Biogas, is de integratie van Europa’s grootste leverancier van biogas voltooid.

Voor het ontstaan van Shell Biogas moeten we eigenlijk eerst een halve eeuw terug in de tijd. In oktober 1973 besluiten de Arabische olieproducerende landen rond de Perzische Golf verenigd in een voorloper van de Opec dat ze meer geld willen voor het “zwarte goud”. Ze verminderen hun olieproductie. Gelijktijdig stellen ze een olieembargo in tegen onder meer Nederland, Groot-Brittannië en de Verenigde Staten. De Opec is kwaad op de landen die Israël openlijk steunen, terwijl de Arabieren – met Egypte en Syrië voorop – juist de Joodse staat waren binnengevallen om gebieden die Israël in 1967 van ze had afgepakt ruimschoots terug te nemen.

In de vijf maanden van het olieembargo stijgt de wereldolieprijs met 300% en treft zo niet alleen de geboycotte naties, maar alle importerende landen. Wat de geschiedenisboeken in gaat als de Eerste Oliecrisis (zie kader Oliecrises onder dit artikel) maakt korte metten met de economische groei van de geïndustrialiseerde landen die kort na het einde van de Tweede Wereldoorlog op gang kwam.

Naar de Noordzee

Door de stijgende inflatie hebben consumenten en bedrijven minder waar voor hun geld, meer mensen verliezen hun baan en de prijzen van zo’n beetje alles worden hoger. Ook de prijzen voor energie stijgen en veel landen gaan op zoek naar alternatieve bronnen. Onder meer Nederland en Groot-Brittannië trekken de Noordzee op, en halen na een lastige start met succes olie en gas uit de zeebodem.

De oliecrisis helpt Noorwegen, dat in 1966 was begonnen met offshore olie- en gaswinning, verder te groeien van een ontwikkelingsland tot een van de rijkste landen ter wereld. Het Scandinavische land wordt energie-exporteur en een belangrijke steunpilaar van de Europese landen voor hun energiebehoefte. In 2024 was zelfs een derde van het Europese aardgas afkomstig uit Noorwegen, mede door de sluiting van de gasvelden in Groningen en de wens van de Europese landen – op Hongarije en Slowakije na – geheel onafhankelijk te zijn van Russisch gas.

Wat is biogas?

Biogas wordt ook wel biomethaan of groen gas genoemd en is kleurloos. Het is een energiebron die gemaakt wordt uit organisch restmateriaal. Het is net aardgas, maar met een veel lagere uitstoot. Eenmaal in het gasnet, draagt het bij aan de verwarming van huizen of de verduurzaming van de industrie. Het kan ook in bijvoorbeeld vloeibaar gemaakte vorm (LNG) worden gebruikt in zwaar transport zoals scheepvaart en vrachtvervoer.

Eerste biogasinstallaties bij Deense boeren

Ook in Denemarken wordt door de Eerste Oliecrisis gezocht naar alternatieve energiebronnen. Uiteindelijk zal het zuidelijkste land van Scandinavië zich vooral richten op windenergie en Noordzeegas, maar dat is niet de enige kaart die het trekt. De agrarische sector is een grote, goedontwikkelde en economisch belangrijke sector in Denemarken. Ook anno 2025 nog, met zo’n 190.000 arbeidsplaatsen en direct verantwoordelijk voor 2,3% van gehele Deense inkomen (BNP). In de jaren 70 worden bij sommige boerenbedrijven in Denemarken de eerste biogasinstallaties gebouwd.

Met wisselend succes, zo schreven de onderzoekers Uffe Jørgensen, Henrik B. Møller en Søren O. Petersen in hun studiewerk dat in 2008 onder meer door de Aarhus Universiteit is gepubliceerd. “Geringe ervaring en slechte technische staat” van de biogasinstallaties worden opgevoerd als argumenten. “Vanaf het einde van de jaren 80 en door de jaren 90 heen werden er een groot aantal installaties gebouwd die meer succes hadden, maar de uitbreiding stagneerde (aan het begin van de 21e eeuw; red.), vooral vanwege slechte bedrijfseconomische omstandigheden.”

IT-bubbel en bankencrisis

Rond de millenniumwisseling wilden bedrijven niet langer investeren, doordat de economie een flinke opdonder kreeg toen wereldwijd het geloof in het kunnen van IT-bedrijven uit elkaar spatte. Vanaf 2004 ging het weer beter, maar in 2008 was de internationale financiële bankencrisis opnieuw een harde klap in het gezicht van de Deense economie en daarmee de bedrijvigheid.

Academische onderzoekers Jørgensen, Møller en Petersen zien wel een lichtpuntje in 2008: het Deense energieakkoord van dat jaar zou biogas nieuw leven inblazen. En eenmaal de financiële crisis van 2008 te boven gaat het hard de goede kant uit met biogas in Denemarken. Volgens cijfers van de Deense energieautoriteit Energistyrelsen was in 2023 al 40 procent van het gas in het Deense leidingnet uit biogas opgewerkt biomethaan, met 100% biomethaan in het gasnetwerk in 2030 als doel. “Daarmee zal het Deense gasverbruik het groenste van Europa zijn”, zegt deze rijksoverheid trots in een verklaring.

(zie ook kader Oliecrises onder dit verhaal)Door de Eerste Oliecrisis wordt gezocht naar alternatieven

Nature Energy sinds 1979 producent van biomethaan

Shell Biogas’ voorloper Nature Energy is dan al sinds 1979 in Denemarken bezig om zich in de markt te zetten als producent van biomethaan. In 2022, als Shell de overname van Nature Energy bekendmaakt, beheert het Deense bedrijf vijftien installaties en heeft het 400 medewerkers. Met hernieuwde investeringen groeide het bedrijf rap van vier biogasinstallaties in 2018 naar Europa’s belangrijkste producent van biogas. In 2022 was de jaarlijkse productie ruim 180 miljoen kubieke meter biogas, dat in samenstelling gelijk is aan het gewone aardgas. Het gemiddeld gasverbruik van de Nederlandse huishouden ligt op zo’n 1.200 m3 per jaar.

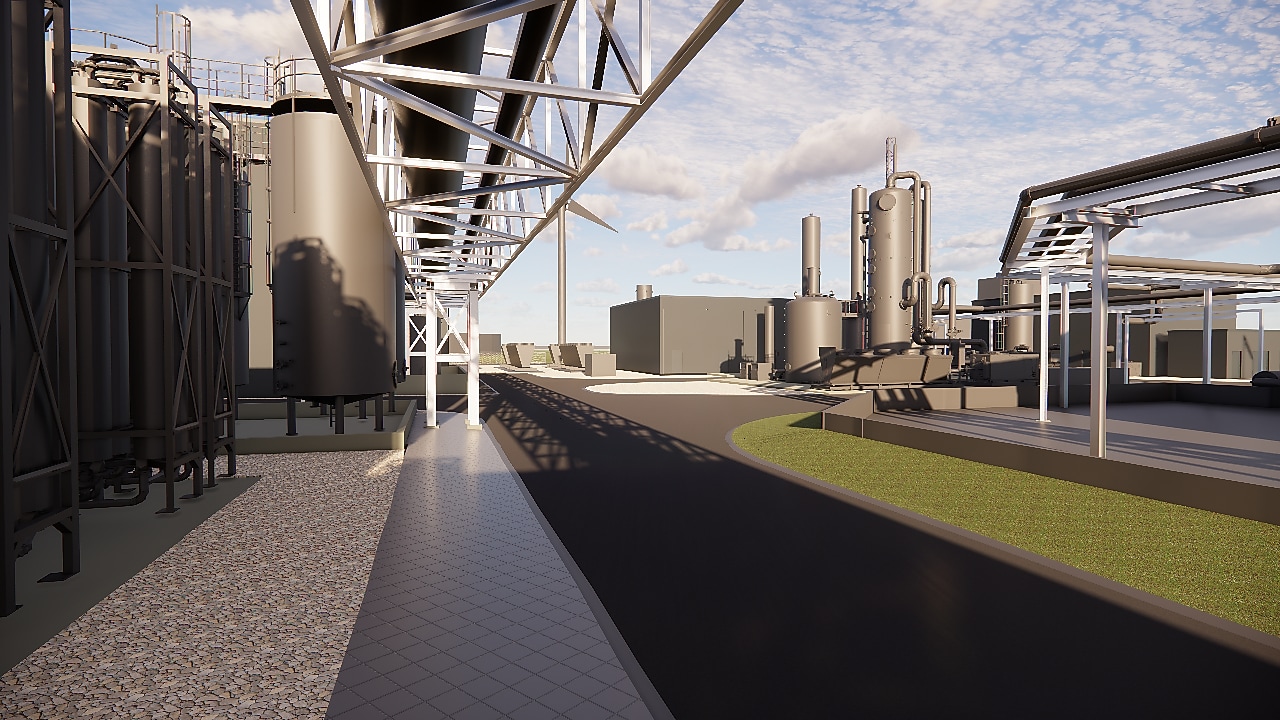

Van de 15 biogasinstallaties van Shell Biogas staan er dertien in Denemarken – waarvan tien op het vasteland Jutland (Jylland). Daarnaast is er een fabriek in Frankrijk en eentje in Almere in Nederland. De fabriek in Almere is wat kleiner dan de standaardinstallatie en ligt tijdelijk stil.

Daarnaast heeft Shell drie nieuwe installaties in Nederland gepland: in Coevorden, in Den Helder en in Emmen. De laatste wordt Northstar genoemd en is een samenwerking met EBN en Engie. Die zouden vanaf 2028 kunnen worden geopend, met de exacte planning afhankelijk van het besluitvormingsproces van gemeenten en inspraakrondes met omwonenden. Biogas wordt in Nederland overigens ook wel groen gas genoemd (zie kader Wat is biogas?).

Shell Biogas in Nederland naar Frans voorbeeld

Net als voor de in september 2024 geopende Sécalia-fabriek van Shell Biogas in het Franse Côte-d’Or in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, zoekt Shell Biogas ook in Nederland actief samenwerking met de boeren in de regio om biogasproductie tot een succes te maken. Voor de Franse fabriek zijn dat 150 agrariërs verenigd onder de naam Dijon Céréales die elk jaar 200.000 ton biologisch restmateriaal leveren. Bij de Sécalia-fabriek is dat voor 90% resten uit de productie van rogge.

Wat vervolgens overblijft in Shells productie van biogas kan ook weer door de boeren worden gebruikt. Dit wordt digestaat genoemd en is een organische meststof. Shell Biogas in Côte-d’Or levert er zo’n 60.000 ton van, dat door Dijon Céréales-boeren op hun akkers wordt gebruikt. Kortom, de productie van biogas draagt bij aan een circulaire, duurzamere bedrijvigheid.

In het nationale aardgasnet

De Franse fabriek is een goed voorbeeld van hoe het ook in Almere, Coevorden en Den Helder kan. En de uit biogas opgewerkte biomethaan wordt in Côte-d’Or in het Franse nationale aardgasnetwerk geïnjecteerd. Iets dat ook moeiteloos in Nederland kan, omdat biogas en aardgas van een vergelijkbare samenstelling zijn.

Shell Biogas maakt onderdeel uit van Shells zogenoemde lage-koolstofoplossingen, doorgaans Low-Carbon Solutions (LCS) genoemd. Europa is daarbij een groeimarkt, mede daar de Europese Unie zich in 2022 tot doel heeft gesteld de biogasproductie in de hele unie te helpen vertienvoudigen in 2030. Volgens de Europese Biogasvereniging zijn er daarvoor duizenden nieuwe biogasinstallaties nodig.

Coevorden, Den Helder en EmmenNieuwe Shell Biogas-installaties in Nederland gepland

Bronnen. Voor dit achtergrondverhaal zijn, behalve medewerkers van Shell Biogas, onder meer de volgende bronnen geraadpleegd: Energistyrelsen, Biogas – en gammelkendt teknologi i front i klimakampen (Aktuel Naturvidenskab, 2008), Danmarks Statistik, Berlingske, The Maritime Executive, Biogas Power ON 2024 (Nature Energy, September 2024), Gaslicht.com

Cautionary note

Cautionary note

The companies in which Shell plc directly and indirectly owns investments are separate legal entities. In this announcement “Shell”, “Shell Group” and “Group” are sometimes used for convenience where references are made to Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general. Likewise, the words “we”, “us” and “our” are also used to refer to Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general or to those who work for them. These terms are also used where no useful purpose is served by identifying the particular entity or entities. ‘‘Subsidiaries’’, “Shell subsidiaries” and “Shell companies” as used in this announcement refer to entities over which Shell plc either directly or indirectly has control. The term “joint venture”, “joint operations”, “joint arrangements”, and “associates” may also be used to refer to a commercial arrangement in which Shell has a direct or indirect ownership interest with one or more parties. The term “Shell interest” is used for convenience to indicate the direct and/or indirect ownership interest held by Shell in an entity or unincorporated joint arrangement, after exclusion of all third-party interest.

Forward-looking Statements

This announcement contains forward-looking statements (within the meaning of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995) concerning the financial condition, results of operations and businesses of Shell. All statements other than statements of historical fact are, or may be deemed to be, forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are statements of future expectations that are based on management’s current expectations and assumptions and involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results, performance or events to differ materially from those expressed or implied in these statements. Forward-looking statements include, among other things, statements concerning the potential exposure of Shell to market risks and statements expressing management’s expectations, beliefs, estimates, forecasts, projections and assumptions. These forward-looking statements are identified by their use of terms and phrases such as “aim”; “ambition”; ‘‘anticipate’’; ‘‘believe’’; “commit”; “commitment”; ‘‘could’’; ‘‘estimate’’; ‘‘expect’’; ‘‘goals’’; ‘‘intend’’; ‘‘may’’; “milestones”; ‘‘objectives’’; ‘‘outlook’’; ‘‘plan’’; ‘‘probably’’; ‘‘project’’; ‘‘risks’’; “schedule”; ‘‘seek’’; ‘‘should’’; ‘‘target’’; ‘‘will’’; “would” and similar terms and phrases. There are a number of factors that could affect the future operations of Shell and could cause those results to differ materially from those expressed in the forward-looking statements included in this announcement, including (without limitation): (a) price fluctuations in crude oil and natural gas; (b) changes in demand for Shell’s products; (c) currency fluctuations; (d) drilling and production results; (e) reserves estimates; (f) loss of market share and industry competition; (g) environmental and physical risks; (h) risks associated with the identification of suitable potential acquisition properties and targets, and successful negotiation and completion of such transactions; (i) the risk of doing business in developing countries and countries subject to international sanctions; (j) legislative, judicial, fiscal and regulatory developments including regulatory measures addressing climate change; (k) economic and financial market conditions in various countries and regions; (l) political risks, including the risks of expropriation and renegotiation of the terms of contracts with governmental entities, delays or advancements in the approval of projects and delays in the reimbursement for shared costs; (m) risks associated with the impact of pandemics, such as the COVID-19 (coronavirus) outbreak, regional conflicts, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, and a significant cybersecurity breach; and (n) changes in trading conditions. No assurance is provided that future dividend payments will match or exceed previous dividend payments. All forward-looking statements contained in this announcement are expressly qualified in their entirety by the cautionary statements contained or referred to in this section. Readers should not place undue reliance on forward-looking statements. Additional risk factors that may affect future results are contained in Shell plc’s Form 20-F for the year ended December 31, 2024 (available at www.shell.com/investors/news-and-filings/sec-filings.html and www.sec.gov). These risk factors also expressly qualify all forward-looking statements contained in this announcement and should be considered by the reader. Each forward-looking statement speaks only as of the date of this announcement, September 25, 2025. Neither Shell plc nor any of its subsidiaries undertake any obligation to publicly update or revise any forward-looking statement as a result of new information, future events or other information. In light of these risks, results could differ materially from those stated, implied or inferred from the forward-looking statements contained in this announcement.

Shell’s Net Carbon Intensity

Also, in this announcement we may refer to Shell’s “Net Carbon Intensity” (NCI), which includes Shell’s carbon emissions from the production of our energy products, our suppliers’ carbon emissions in supplying energy for that production and our customers’ carbon emissions associated with their use of the energy products we sell. Shell’s NCI also includes the emissions associated with the production and use of energy products produced by others which Shell purchases for resale. Shell only controls its own emissions. The use of the terms Shell’s “Net Carbon Intensity” or NCI are for convenience only and not intended to suggest these emissions are those of Shell plc or its subsidiaries.

Shell’s net-zero emissions target

Shell’s operating plan, outlook and budgets are forecasted for a ten-year period and are updated every year. They reflect the current economic environment and what we can reasonably expect to see over the next ten years. Accordingly, they reflect our Scope 1, Scope 2 and NCI targets over the next ten years. However, Shell’s operating plans cannot reflect our 2050 net-zero emissions target, as this target is currently outside our planning period. In the future, as society moves towards net-zero emissions, we expect Shell’s operating plans to reflect this movement. However, if society is not net zero in 2050, as of today, there would be significant risk that Shell may not meet this target.

Forward-looking non-GAAP measures

This announcement may contain certain forward-looking non-GAAP measures such as cash capital expenditure and divestments. We are unable to provide a reconciliation of these forward-looking non-GAAP measures to the most comparable GAAP financial measures because certain information needed to reconcile those non-GAAP measures to the most comparable GAAP financial measures is dependent on future events some of which are outside the control of Shell, such as oil and gas prices, interest rates and exchange rates. Moreover, estimating such GAAP measures with the required precision necessary to provide a meaningful reconciliation is extremely difficult and could not be accomplished without unreasonable effort. Non-GAAP measures in respect of future periods which cannot be reconciled to the most comparable GAAP financial measure are calculated in a manner which is consistent with the accounting policies applied in Shell plc’s consolidated financial statements.

The contents of websites referred to in this announcement do not form part of this announcement.

We may have used certain terms, such as resources, in this announcement that the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) strictly prohibits us from including in our filings with the SEC. Investors are urged to consider closely the disclosure in our Form 20-F, File No 1-32575, available on the SEC website www.sec.gov

Oliecrises

De Eerste Oliecrisis

In oktober 1973 ging de olieprijs ineens fors omhoog en was er de angst voor tekorten die vervolgens een economische schokgolf tot gevolg had. Dit nadat de Arabische olieproducerende landen verendigd in een voorloper van de Opec besloten de productie elke maand met 5% te verlagen in de hoop zo de prijs op te stuwen. Tegelijkertijd kondigden ze een olieboycot af tegen Nederland, Groot-Brittannië, Portugal, de Verenigde Staten, Canada en Zuid-Afrika omdat die landen Israël openlijk steunen in de oorlog die de Arabische landen in 1973 met de Joodse staat voeren. Die Jom Kipoeroorlog is dan weer een reactie op Israëls bezetting van gebieden in 1967. De boycot wordt in maart 1974 geschrapt tijdens onderhandelingen in Washington, maar dan is het leed voor de economie van de geïndustraliseerde landen al geschied.

De Tweede Oliecrisis

Als in 1979 tijdens de Iraanse revolutie de islamitische ayatollahs onder leiding van Ruhollah Khomeini de macht grijpen in Teheran, is dat het begin van de Tweede Oliecrisis. Opnieuw stijgen de olieprijzen snel en zullen door de daaropvolgende door Irak begonnen achtjarige oorlog met Iran vaker onder druk komen te staan. De olie-export vanuit Iran ligt na de Iraanse revolutie een stuk lager dan ervoor.

Nederland en de oliecrises

In Nederland leiden de oliecrises tot autoloze zondagen om zo brandstof te sparen. Ook gaat Nederland harder op zoek naar vooral gas en olie uit de Noordzee. NAM, de 50/50-joint venture van Shell en Exxon Mobil, speelt daarbij een sleutelrol.

Shell Biogas and Dutch ambitions: leading renewable gas thanks to Danish common sense

25 Sep. 2025

Imagine running a farm. The rye and wheat from your land end up in the bread that feeds people. But the leaves and stems of the crops—those are not very useful. Enter Shell Biogas, the new name (as of September) for the originally Danish company Nature Energy. In Denmark, biogas has a long tradition. In countries like the Netherlands, it is less established, but Shell aims to expand its presence here over the coming years with the alternative for natural gas.

Text: Marcel Burger, with contribution on the French biogas plant by Molly Lynch.

Photography: ANP/HH/Marcel Berendsen, Shell Biogas/Claus Haagensen, AdobeStock.

UPDATE 2 Oct. 2025 in paragraph Nature Energy since 1979 producer of biomethane added Northstar in Emmen

Shell announced its acquisition of Nature Energy in November 2022. Now that the name has officially changed to Shell Biogas, the integration of Europe’s largest biogas supplier is complete.

To understand the origins of Shell Biogas, we actually need to go back half a century. In October 1973, the Arab oil-producing countries around the Persian Gulf—united in a precursor to OPEC—decide they want more money for their “black gold”. They reduce oil production and simultaneously impose an oil embargo on countries including the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and the United States. OPEC is angry at these nations for openly supporting Israel, while the Arab states—led by Egypt and Syria—had just invaded the Jewish state to reclaim territories that Israel had taken from them in 1967.

During the five months of the oil embargo, the global oil price rise by 300%, affecting not only the boycotted nations but all oil-importing countries. What entered the history books as the First Oil Crisis (see the frame “Oil Crises” below the article) abruptly ends the post–World War II economic growth of industrialised nations.

To the North Sea

Due to rising inflation, consumers and businesses are getting less value for their money, more people are losing their jobs, and the prices of nearly everything go up. Energy prices are rising as well, prompting many countries to seek alternative sources. Among them the Netherlands and the United Kingdom, with both nations seting course to the North Sea and, after a challenging start, successfully extract oil and gas from the seabed.

The oil crisis benefits Norway, which began offshore oil and gas production in 1966. It helps the country grow from a developing nation into one of the richest in the world. The Scandinavian country becomes an energy exporter and a key pillar supporting European nations in meeting their energy needs. In 2024, one-third of Europe’s natural gas came from Norway—partly due to the closure of the Groningen gas fields in the Netherlands and the desire of European countries (except Hungary and Slovakia) to become completely independent from Russian gas.

What is biogas?

Biogas, also known as biomethane or renewable gas, is colourless. It is an energy source produced from organic residual material. It is similar to natural gas but with much lower emissions. Once injected into the gas grid, it contributes to heating homes or making industry more sustainable. It can also be used in liquefied form (LNG), for example, in heavy-duty transport such as shipping and freight transport.

First biogas installations at Danish farms

Following the First Oil Crisis, Denmark also begins searching for alternative energy sources. Ultimately, the southernmost country in Scandinavia would focus primarily on wind energy and North Sea gas—but that was not its only strategy. Agriculture is a large, well-developed, and economically significant sector in Denmark. Even in 2025, it accounts for around 190,000 jobs and directly contributes 2.3% to Denmark’s total income (GDP).

In the 1970s, the first biogas installations are built on some Danish farms. Their success varies, as noted by researchers Uffe Jørgensen, Henrik B. Møller, and Søren O. Petersen in a study published in 2008, published by Aarhus University. They cite “limited experience and poor technical condition” of the biogas systems as key issues. “From the late 1980s through the 1990s, a large number of installations were built that were more successful, but expansion stagnated (in the early 21st century), mainly due to poor economic conditions.”

IT bubble and Banking Crisis

Around the turn of the millennium, companies stop investing as the economy takes a major hit when global confidence in the capabilities of IT companies collapsed. Things begin to improve again in 2004, but in 2008 the international financial banking crisis delivers another heavy blow to the Danish economy and its business activity.

However, academic researchers Jørgensen, Møller, and Petersen see a silver lining in 2008: the Danish energy agreement of that year breaths new life into biogas. And once Denmark recovers from the 2008 financial crisis, biogas development accelerates significantly. According to figures from the Danish Energy Agency (Energistyrelsen), by 2023, 40% of the gas in Denmark’s pipeline network was upgraded biogas (biomethane), with the goal of reaching 100% biomethane in the gas grid by 2030. “This will make Denmark’s gas consumption the most renewable in Europe,” the national government proudly states in a declaration.

(see also the frame Oil crises underneath this story)Following the First Oil Crisis the search for alternative energy sources begins

Nature Energy: biomethane producer since 1979

Shell Biogas’ predecessor, Nature Energy, has been working to establish itself in the Danish market as a biomethane producer since 1979. By 2022, when Shell announced its acquisition of the company, Nature Energy operated fifteen installations and employed 400 people. With renewed investments, the company grew rapidly—from four biogas plants in 2018 to becoming Europe’s leading biogas producer.

In 2022, its annual production exceeded 180 million cubic metres (6.4 billion cubic feet) of biogas, which has the same composition as conventional natural gas. For comparison, households in the Netherlands—a natural gas high-usage country—need about 1,200 m³ (42,377.6 ft³) gas per year.

Of Shell Biogas’ fifteen plants, thirteen are located in Denmark—ten of which are on the mainland, Jutland (Jylland). There is also one plant in France and one in Almere, the Netherlands. The Almere facility is slightly smaller than the standard installation and is currently temporarily idle.

Shell also has three new installations planned in the Netherlands: one in Coevorden in the northeast, one in Den Helder in the northwest of the country, and one in Emmen in the northeast. The latter is called Northstar and is a cooperation with partners EBN and Engie. These could open as early as 2028, depending on municipal decision-making processes and public consultation rounds. In the Netherlands, biogas is commonly referred to as “green gas” (see box: What is biogas?).

Shell Biogas in the Netherlands Inspired by the French Model

Shell Biogas is also actively seeking collaboration with local farmers in the Netherlands to make biogas production a success. Just like with the Sécalia plant opened in September 2024 by Shell Biogas in the Côte-d’Or region of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté, in the central eastern part of France. For the French plant, 150 farmers—organised under the name Dijon Céréales—supply 200,000 tons of organic residual material each year. At the Sécalia facility, 90% of that comes from rye production leftovers.

What remains after Shell’s biogas production can be reused by the farmers. This byproduct is called digestate, an organic fertiliser. Shell Biogas in Côte-d’Or supplies around 60,000 tonnes of it, which is used by Dijon Céréales farmers on their fields. In short, biogas production contributes to a circular, more sustainable form of business.

Into the National Gas Grid

The French plant is a good example of what could also be achieved in the Dutch municipalities of Almere, Coevorden, and Den Helder. The biomethane upgraded from biogas in Côte-d’Or is injected into the French national natural gas network—something that can also be done effortlessly in the Netherlands—since biogas and natural gas have a similar composition.

Shell Biogas is part of Shell’s Low-Carbon Solutions (LCS). Europe is a growth market in this regard, especially since the European Union set a goal in 2022 to help increase biogas production tenfold across the EU by 2030. According to the European Biogas Association, thousands of new biogas installations will be needed to achieve this.

Sources. This background story has been written using among the sources employees of Shell Biogas, and also the following references: Energistyrelsen, Biogas – en gammelkendt teknologi i front i klimakampen (Aktuel Naturvidenskab, 2008), Danmarks Statistik, Berlingske, The Maritime Executive, Biogas Power ON 2024 (Nature Energy, September 2024), Gaslicht.com

In Coevorden, Den Helder and EmmenNew Shell Biogas installations in the Netherlands are planned

Cautionary note

Cautionary note

The companies in which Shell plc directly and indirectly owns investments are separate legal entities. In this announcement “Shell”, “Shell Group” and “Group” are sometimes used for convenience where references are made to Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general. Likewise, the words “we”, “us” and “our” are also used to refer to Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general or to those who work for them. These terms are also used where no useful purpose is served by identifying the particular entity or entities. ‘‘Subsidiaries’’, “Shell subsidiaries” and “Shell companies” as used in this announcement refer to entities over which Shell plc either directly or indirectly has control. The term “joint venture”, “joint operations”, “joint arrangements”, and “associates” may also be used to refer to a commercial arrangement in which Shell has a direct or indirect ownership interest with one or more parties. The term “Shell interest” is used for convenience to indicate the direct and/or indirect ownership interest held by Shell in an entity or unincorporated joint arrangement, after exclusion of all third-party interest.

Forward-looking Statements

This announcement contains forward-looking statements (within the meaning of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995) concerning the financial condition, results of operations and businesses of Shell. All statements other than statements of historical fact are, or may be deemed to be, forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are statements of future expectations that are based on management’s current expectations and assumptions and involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results, performance or events to differ materially from those expressed or implied in these statements. Forward-looking statements include, among other things, statements concerning the potential exposure of Shell to market risks and statements expressing management’s expectations, beliefs, estimates, forecasts, projections and assumptions. These forward-looking statements are identified by their use of terms and phrases such as “aim”; “ambition”; ‘‘anticipate’’; ‘‘believe’’; “commit”; “commitment”; ‘‘could’’; ‘‘estimate’’; ‘‘expect’’; ‘‘goals’’; ‘‘intend’’; ‘‘may’’; “milestones”; ‘‘objectives’’; ‘‘outlook’’; ‘‘plan’’; ‘‘probably’’; ‘‘project’’; ‘‘risks’’; “schedule”; ‘‘seek’’; ‘‘should’’; ‘‘target’’; ‘‘will’’; “would” and similar terms and phrases. There are a number of factors that could affect the future operations of Shell and could cause those results to differ materially from those expressed in the forward-looking statements included in this announcement, including (without limitation): (a) price fluctuations in crude oil and natural gas; (b) changes in demand for Shell’s products; (c) currency fluctuations; (d) drilling and production results; (e) reserves estimates; (f) loss of market share and industry competition; (g) environmental and physical risks; (h) risks associated with the identification of suitable potential acquisition properties and targets, and successful negotiation and completion of such transactions; (i) the risk of doing business in developing countries and countries subject to international sanctions; (j) legislative, judicial, fiscal and regulatory developments including regulatory measures addressing climate change; (k) economic and financial market conditions in various countries and regions; (l) political risks, including the risks of expropriation and renegotiation of the terms of contracts with governmental entities, delays or advancements in the approval of projects and delays in the reimbursement for shared costs; (m) risks associated with the impact of pandemics, such as the COVID-19 (coronavirus) outbreak, regional conflicts, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, and a significant cybersecurity breach; and (n) changes in trading conditions. No assurance is provided that future dividend payments will match or exceed previous dividend payments. All forward-looking statements contained in this announcement are expressly qualified in their entirety by the cautionary statements contained or referred to in this section. Readers should not place undue reliance on forward-looking statements. Additional risk factors that may affect future results are contained in Shell plc’s Form 20-F for the year ended December 31, 2024 (available at www.shell.com/investors/news-and-filings/sec-filings.html and www.sec.gov). These risk factors also expressly qualify all forward-looking statements contained in this announcement and should be considered by the reader. Each forward-looking statement speaks only as of the date of this announcement, September 25, 2025. Neither Shell plc nor any of its subsidiaries undertake any obligation to publicly update or revise any forward-looking statement as a result of new information, future events or other information. In light of these risks, results could differ materially from those stated, implied or inferred from the forward-looking statements contained in this announcement.

Shell’s Net Carbon Intensity

Also, in this announcement we may refer to Shell’s “Net Carbon Intensity” (NCI), which includes Shell’s carbon emissions from the production of our energy products, our suppliers’ carbon emissions in supplying energy for that production and our customers’ carbon emissions associated with their use of the energy products we sell. Shell’s NCI also includes the emissions associated with the production and use of energy products produced by others which Shell purchases for resale. Shell only controls its own emissions. The use of the terms Shell’s “Net Carbon Intensity” or NCI are for convenience only and not intended to suggest these emissions are those of Shell plc or its subsidiaries.

Shell’s net-zero emissions target

Shell’s operating plan, outlook and budgets are forecasted for a ten-year period and are updated every year. They reflect the current economic environment and what we can reasonably expect to see over the next ten years. Accordingly, they reflect our Scope 1, Scope 2 and NCI targets over the next ten years. However, Shell’s operating plans cannot reflect our 2050 net-zero emissions target, as this target is currently outside our planning period. In the future, as society moves towards net-zero emissions, we expect Shell’s operating plans to reflect this movement. However, if society is not net zero in 2050, as of today, there would be significant risk that Shell may not meet this target.

Forward-looking non-GAAP measures

This announcement may contain certain forward-looking non-GAAP measures such as cash capital expenditure and divestments. We are unable to provide a reconciliation of these forward-looking non-GAAP measures to the most comparable GAAP financial measures because certain information needed to reconcile those non-GAAP measures to the most comparable GAAP financial measures is dependent on future events some of which are outside the control of Shell, such as oil and gas prices, interest rates and exchange rates. Moreover, estimating such GAAP measures with the required precision necessary to provide a meaningful reconciliation is extremely difficult and could not be accomplished without unreasonable effort. Non-GAAP measures in respect of future periods which cannot be reconciled to the most comparable GAAP financial measure are calculated in a manner which is consistent with the accounting policies applied in Shell plc’s consolidated financial statements.

The contents of websites referred to in this announcement do not form part of this announcement.

We may have used certain terms, such as resources, in this announcement that the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) strictly prohibits us from including in our filings with the SEC. Investors are urged to consider closely the disclosure in our Form 20-F, File No 1-32575, available on the SEC website www.sec.gov

Oil crises

The First Oil Crisis

In October 1973, oil prices suddenly rose sharply, sparking fears of shortages and triggering an economic shockwave. This happened after the Arab oil-producing countries, united in a precursor to OPEC, decided to cut production by 5% each month to drive up prices. At the same time, they announced an oil embargo against the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Portugal, the United States, Canada, and South Africa because those countries openly supported Israel in the war being fought between Arab nations and the Jewish state in 1973. That Yom Kippur War was itself a reaction to Israel’s occupation of territories in 1967. The embargo was lifted in March 1974 during negotiations in Washington, but by then the damage to the economies of industrialised nations had already been done.

The Second Oil Crisis

In 1979, during the Iranian Revolution, Islamic ayatollahs led by Ruhollah Khomeini seized power in Tehran, marking the beginning of the Second Oil Crisis. Once again, oil prices rose rapidly and would remain under pressure due to the eight-year war that Iraq initiated against Iran at the time. After the revolution, Iran’s oil exports were significantly lower than before.

the Netherlands and the oil crises

In the Netherlands, the oil crises led to car-free Sundays to conserve fuel. The country also intensified its search for oil and gas, particularly in the North Sea. NAM, the 50/50 joint venture of Shell and ExxonMobil, played a key role in this effort.