Derde jeugd voor de Noordzee

Lang leek de Noordzee een plek waar steeds minder aardgas gewonnen zou gaan worden. Maar sinds 2022 is met het terugschroeven van de Russische gastoevoer naar Europa en de scherp hogere energieprijzen het beeld gekeerd. De Noordzee is voor de derde keer terug in beeld als bron van olie en gas.

Tekst: Rob van 't Wel, aanvulling door Marcel Burger.

Infographic: Dirk Jan Pino. Beeld: Shell plc., Stuart Conway, A/S Norske Shell.

Originele publicatie: 30 nov 2022. Geactualiseerd en aangevuld: 9 jan 2026.

Wie op internet de zoekwoorden ‘Noordzee’ en ‘offshore’ intikt, krijgt als eerste zoekresultaten een keur van hits over windparken. Het zegt iets over het belang van de windenergie als duurzame energiebron. En het zegt tegelijkertijd iets over de afgenomen aandacht voor de olie- en gaswinning op zee.

Het kan verkeren. Lang leek de winning van olie en gas op de Noordzee een voorbeeld van een bedrijfstak die tot uitsterven gedoemd was. De ‘grote jongens’ uit de energiesector bouwden op de Noordzee hun activiteiten af en lieten de kruimels achter voor de kleinere spelers die nog brood zagen in het opruimen en winnen van de laatste restjes. Dat beeld is als gevolg van de oorlog in Oekraïne in rap tempo ietwat gekanteld. De hoge energieprijzen openen mogelijkheden voor nieuwe, winstgevende activiteiten. Daarnaast zijn overheden op zoek naar een vermindering van de afhankelijkheid van onbetrouwbare leveranciers.

Shell op de Noordzee

Shell heeft een lange traditie in de offshore olie- en gasindustrie op de Noordzee, vooral via NAM. Daarnaast is het concern sinds 2019 ook zeer actief in windenergie, met inmiddels ons vierde windpark voor de Nederlandse kust in aanbouw.

Meer weten?

Rode draad

Het is de rode draad voor de ontwikkeling van de Noordzee als winningsgebied van olie en gas. De eerste golf van investeringen gaat terug tot het najaar van 1956 als de Suezcrisis uitbreekt. Hoewel er een reeks aan redenen is waarom de spanningen destijds groeien, vormt de nationalisering van het Suezkanaal door de Egyptische president Gamal Abdel Nasser de directe aanleiding voor een gewapend conflict. Als gevolg hiervan komt de olieexport van het Midden-Oosten richting Europa in het nauw.

Die afhankelijkheid is de aanzet voor het zoeken naar alternatieven en zo komt de Noordzee in beeld. Maar van wie is die potentiële rijkdom? Alle olie-activiteiten beginnen daarom aan de tafels van diplomaten. Twee jaar na de Suezcrisis wordt in het Zwitserse Genève het zogenoemde Verdrag inzake het continentale plateau gesloten. De overeenkomst legt de grenzen vast voor de verdeling van de Noordzee en daarmee de rechten voor exploratie en productie van de fossiele bodemschatten.

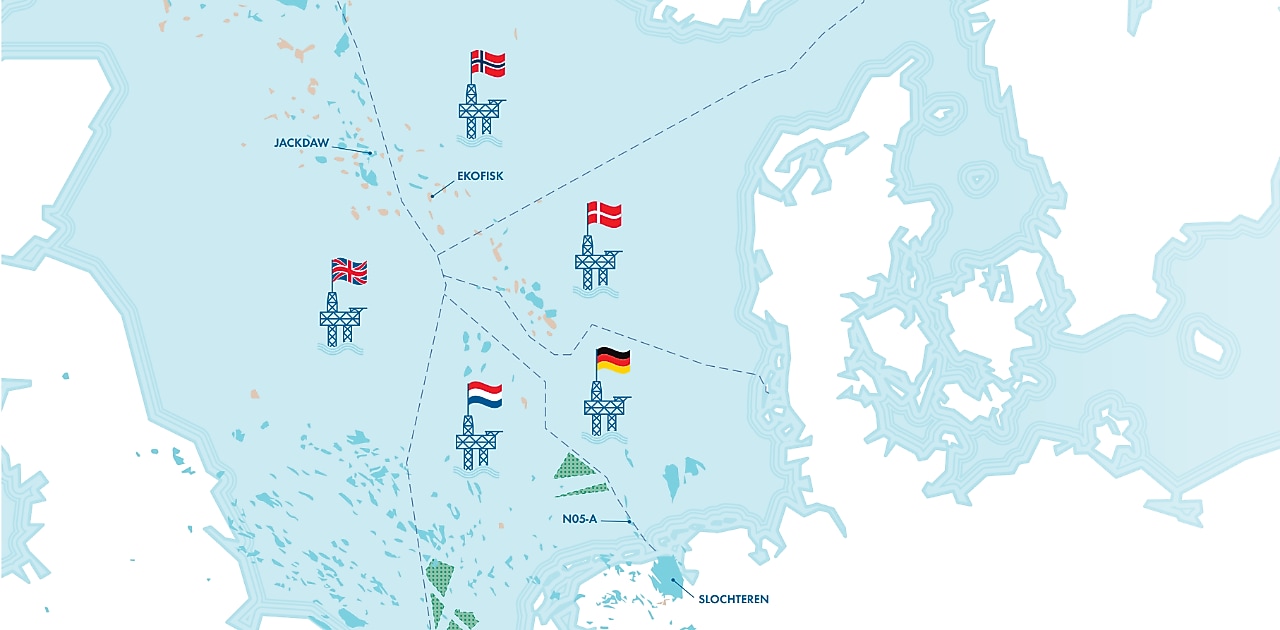

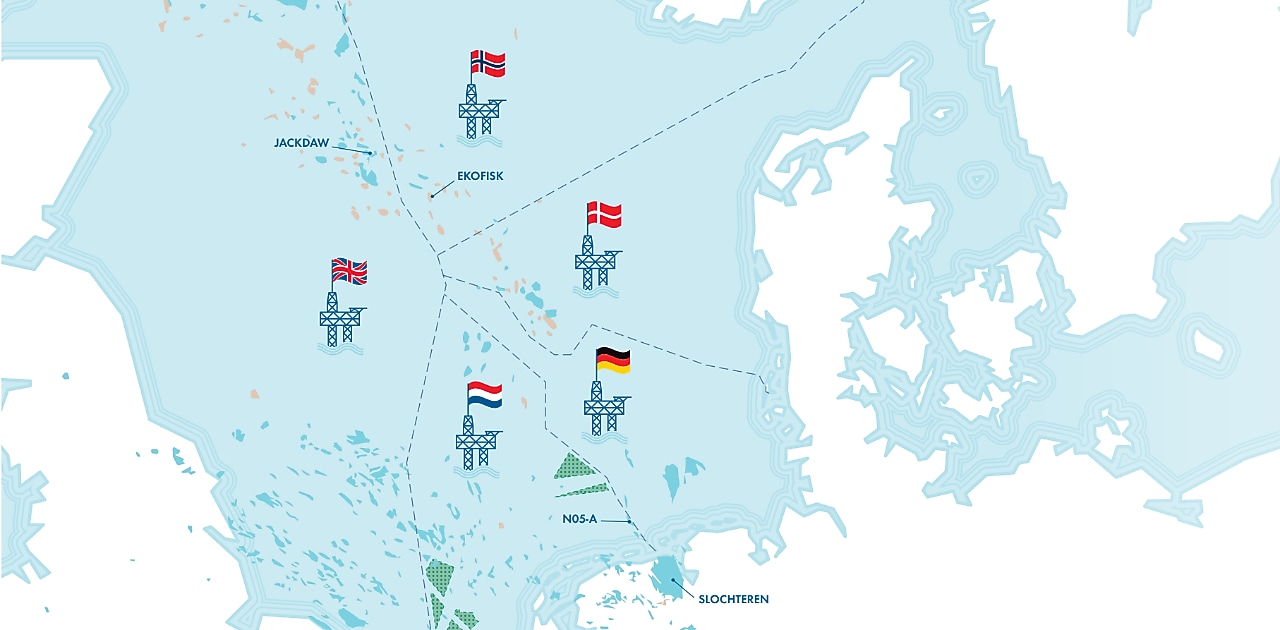

Mede door de olie- en gasvondsten op het omliggende vasteland, met als parel in de kroon de vondst van het Groningenveld in 1959, ontstaat er in de loop van de jaren 60 op zee een felle jacht op olie en gas. Met matig resultaat overigens, wat leidt tot een afname van het enthousiasme. Dat verandert in december 1969 als in het Noorse deel van de Noordzee het Ekofisk-gasveld wordt aangeboord. In diezelfde maand wordt ook een behoorlijk olieveld in de Schotse wateren gevonden.

Bonanza

Het Verenigd Koninkrijk en Noorwegen blijken de belangrijkste winnaars van de offshore bonanza. Daar vinden dan ook de grote investeringen plaats, al verandert dat door een volgende onzekere periode van olieleveranties: de energiecrises van 1973 en 1979. Die zijn het gevolg van opnieuw opgelopen spanningen in het Midden-Oosten en het dichtdraaien van de oliekraan door belangrijke Arabische producenten.

Als reactie daarop gaan regeringen van Noordzeelanden de investeringen op de Noordzee stimuleren. Dat leidt in Nederland al in 1974 tot het opzetten van het zogeheten kleineveldenbeleid. Het belangrijkste element daarvan is dat er voor geproduceerd Noordzeegas altijd een koper is. Die zekerheid leidt tot een nieuwe investeringsgolf, omdat Noordzeeproducenten daarmee niet meer hoeven te concurreren met bijvoorbeeld het Gronings gas, waarvan de productiekosten aanzienlijk lager liggen.

Die gloriejaren ebben over de gehele Noordzee langzaam maar zeker weg, ook omdat de eerste grote velden op het einde van hun productietijd lopen. De gemakkelijke velden zijn gevonden, over hun top, fossiel ligt onder druk en windparken vragen ruimte en investeringen. Bovendien komt er in de loop van deze eeuw steeds meer concurrerend gas uit Rusland. De Noordzee lijkt steeds meer een uitstervende energieprovincie te worden. Grote spelers verkopen hun belangen steeds vaker aan kleinere partijen die vooral gefinancierd worden met kapitaal van durfinvesteerders.

Herkomst verbruikt aardgas in Nederland 2024

Van al het verbruikte aardgas in Nederland in 2024 kwam 38% nog gewoon uit de Nederlandse velden. Voorts kwam bijna een derde (27%) als LNG uit de Verenigde Staten. Noorwegen zorgde voor 14% van het gas dat Nederland nodig had, en de rest van de EU voor nog eens 6%. Tot slot kwam 13% van buiten de EU, Noorwegen en de VS, en nog eens 2% kwam uit Rusland.

Bron: EBN

Groen licht

Opnieuw zet een ‘wereldgebeurtenis’ de Noordzee terug op de kaart en geeft de zee daarmee haar derde jeugd. Op donderdag 24 februari 2022 valt Rusland Oekraïne binnen. De afhankelijkheid van energieleverancier Rusland komt genadeloos aan het licht. Embargo’s en politiek gesteggel doen de rest: de prijs van energie gaat van record naar record. Het maakt dat de regeringen van de Noordzeelanden opnieuw naar de Noordzee kijken om de afhankelijkheid van andere exporteurs te verminderen.

In april 2022 maakt het Nederlandse kabinet bekend de gasproductie voor de kust te willen vergemakkelijken. Een week later klinkt hetzelfde geluid uit Denemarken, net na Groot-Brittannië. De markt omarmt die koerswijzigingen. Samen met de hoge gasprijzen die investeringen zekerder en rendabeler maken, zijn inmiddels de nodige investeringsbeslissingen genomen. Zo laat Shell eind mei 2022 weten het grote Jackdaw-veld, 250 kilometer uit de kust van Aberdeen, te gaan ontwikkelen. Eenmaal in productie zou het gasveld goed moeten zijn voor 6% van de Britse gasbehoefte.

Versnellingsbrief

Uit de zogeheten ‘versnellingsbrief’ die staatssecretaris van Mijnbouw Hans Vijlbrief half juli 2022 naar de Tweede Kamer stuurt, blijkt dat hij in eerste instantie vooral inzet op een versoepeling van het vergunningenproces voor nieuwe boringen. Op die manier kan de Noordzee naar zijn zeggen “een essentiële rol spelen in het beperken van onze importafhankelijkheid”. “De energietransitie”, zo schrijft hij, “is namelijk niet van de ene dag op de andere dag geregeld.”

De versoepeling van de procedures moet tot extra gaswinning op zee leiden. Gas dat, omdat het transport veel minder energie vraagt en de winning moderner is, per saldo een lagere belasting van CO2-uitstoot heeft.

En gas dat de Nederlandse schatkist ook extra inkomsten oplevert. In 2021 kwam er in Nederland 8,9 miljard kuub aardgas van de Noordzee. Door de versnelling zou er volgens de bewindsman in 2022 er jaarlijks 2 tot 4 miljard kuub aan kunnen worden toegevoegd. Dat is naar zijn inschatting voor op een termijn van vijf jaar. Het jaarlijks gasverbruik in Nederland is dan zo’n 40 miljard kuub. Vijlbrief kondigt in zijn versnellingsbrief aan ook te kijken naar financiële prikkels voor investeringen en een andere rol van staatsbedrijf Energie Beheer Nederland (EBN).

Buitenlands aardgas in Nederland in kubieke meter (bcm)

Nog steeds komt er veel aardgas uit de Nederlandse bodem (zie kader hierboven), namelijk uit de zogenoemde kleine velden en uit de Noordzee. Maar steeds vaker komt aardgas uit het buitenland. In 2024 waren de volgende landen de grootste leveranciers van geïmporteerd gas: Verenigde Staten (14,43 miljard kuub, vooral LNG), Noorwegen (7.84 kuub, vooral via pijpleiding), Duitsland (5,8 kuub, vooral via pijpleiding als doorvoerland), België (4,2 kuub, via vooral pijpleiding als doorvoerland), Rusland (1,92 kuub als LNG).

Bronnen: CBS, IEEFA

Nederlands gas daalt verder

Maar de Nederlandse gasproductie daalt na die "Versnellingsbrief" verder. In 2023 is die zelfs 10% minder dan verwacht, blijkt uit onderzoek van TNO. Dat geldt dan voor de zogenoemde 'kleine velden': alle gasvelden zonder het Groningen-gasveld.

De Nederlandse regering onderneemt opnieuw actie en sluit in april 2025 in Scheveningen een akkoord met Energie Beheer Nederland (EBN) en branchevereniging Element NL om het resterende (potentiële) aardgas op de Noordzee verantwoord te winnen. Sophie Hermans, die dan Minister van Klimaat en Groene Groei (KGG) is, ondertekent namens het kabinet dit Sectorakkoord gaswinning in de energietransitie.

Jeugd met strubbelingen

De derde jeugd van de Noordzee gaat gepaard met wat strubbelingen. Na wat vertraging door juridische procedures blijft Jackdaw een nieuw initiatief voor het Britse deel van de Noordzee. In Noorwegen blijft Shell een stabiele en betrouwbare gasleverancier voor Europa, als partner in Troll en als uitbater van Ormen Lange – de grootste gasvelden op het Noorse continentale plat.

In het Nederlandse deel van de Noordzee werd in 2024 werd voor het eerst sinds 2002 nagenoeg voldoende gasvoorraad op zee aangetoond om de daling in de jaarlijkse productie van de afgelopen tijd met 95% te gaan compenseren, stelt TNO. De totaal bewezen gasvoorraad op zee schat TNO eind 2024 op 40 miljard 'kuub'.

Hoe Vikinggas naar Nederland blijft stromen

Vandaag de dag is Ormen Lange in omvang het tweede offshore gaswinningsproject van Noorwegen én draagt sterk bij aan Europa’s energieleveringszekerheid. En juist op Ormen Lange hebben ingenieurs recent een knap staaltje diepzeewerk verricht om de gaswinning op peil te houden.

Cautionary note

Cautionary note

The companies in which Shell plc directly and indirectly owns investments are separate legal entities. In this story “Shell”, “Shell Group” and “Group” are sometimes used for convenience where references are made to Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general. Likewise, the words “we”, “us” and “our” are also used to refer to Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general or to those who work for them. These terms are also used where no useful purpose is served by identifying the particular entity or entities. ‘‘Subsidiaries’’, “Shell subsidiaries” and “Shell companies” as used in this announcement refer to entities over which Shell plc either directly or indirectly has control. The term “joint venture”, “joint operations”, “joint arrangements”, and “associates” may also be used to refer to a commercial arrangement in which Shell has a direct or indirect ownership interest with one or more parties. The term “Shell interest” is used for convenience to indicate the direct and/or indirect ownership interest held by Shell in an entity or unincorporated joint arrangement, after exclusion of all third-party interest.

Forward-looking Statements

This story contains forward-looking statements (within the meaning of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995) concerning the financial condition, results of operations and businesses of Shell. All statements other than statements of historical fact are, or may be deemed to be, forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are statements of future expectations that are based on management’s current expectations and assumptions and involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results, performance or events to differ materially from those expressed or implied in these statements. Forward-looking statements include, among other things, statements concerning the potential exposure of Shell to market risks and statements expressing management’s expectations, beliefs, estimates, forecasts, projections and assumptions. These forward-looking statements are identified by their use of terms and phrases such as “aim”; “ambition”; ‘‘anticipate’’; ‘‘believe’’; “commit”; “commitment”; ‘‘could’’; ‘‘estimate’’; ‘‘expect’’; ‘‘goals’’; ‘‘intend’’; ‘‘may’’; “milestones”; ‘‘objectives’’; ‘‘outlook’’; ‘‘plan’’; ‘‘probably’’; ‘‘project’’; ‘‘risks’’; “schedule”; ‘‘seek’’; ‘‘should’’; ‘‘target’’; ‘‘will’’; “would” and similar terms and phrases. There are a number of factors that could affect the future operations of Shell and could cause those results to differ materially from those expressed in the forward-looking statements included in this story, including (without limitation): (a) price fluctuations in crude oil and natural gas; (b) changes in demand for Shell’s products; (c) currency fluctuations; (d) drilling and production results; (e) reserves estimates; (f) loss of market share and industry competition; (g) environmental and physical risks; (h) risks associated with the identification of suitable potential acquisition properties and targets, and successful negotiation and completion of such transactions; (i) the risk of doing business in developing countries and countries subject to international sanctions; (j) legislative, judicial, fiscal and regulatory developments including regulatory measures addressing climate change; (k) economic and financial market conditions in various countries and regions; (l) political risks, including the risks of expropriation and renegotiation of the terms of contracts with governmental entities, delays or advancements in the approval of projects and delays in the reimbursement for shared costs; (m) risks associated with the impact of pandemics, such as the COVID-19 (coronavirus) outbreak, regional conflicts, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, and a significant cybersecurity breach; and (n) changes in trading conditions. No assurance is provided that future dividend payments will match or exceed previous dividend payments. All forward-looking statements contained in this story are expressly qualified in their entirety by the cautionary statements contained or referred to in this section. Readers should not place undue reliance on forward-looking statements. Additional risk factors that may affect future results are contained in Shell plc’s Form 20-F for the year ended December 31, 2024 (available at www.shell.com/investors/news-and-filings/sec-filings.html and www.sec.gov). These risk factors also expressly qualify all forward-looking statements contained in this story and should be considered by the reader. Each forward-looking statement speaks only as of the date of this story, January 9, 2026. Neither Shell plc nor any of its subsidiaries undertake any obligation to publicly update or revise any forward-looking statement as a result of new information, future events or other information. In light of these risks, results could differ materially from those stated, implied or inferred from the forward-looking statements contained in this story.

Shell’s Net Carbon Intensity

Also, in this story we may refer to Shell’s “Net Carbon Intensity” (NCI), which includes Shell’s carbon emissions from the production of our energy products, our suppliers’ carbon emissions in supplying energy for that production and our customers’ carbon emissions associated with their use of the energy products we sell. Shell’s NCI also includes the emissions associated with the production and use of energy products produced by others which Shell purchases for resale. Shell only controls its own emissions. The use of the terms Shell’s “Net Carbon Intensity” or NCI are for convenience only and not intended to suggest these emissions are those of Shell plc or its subsidiaries.

Shell’s net-zero emissions target

Shell’s operating plan, outlook and budgets are forecasted for a ten-year period and are updated every year. They reflect the current economic environment and what we can reasonably expect to see over the next ten years. Accordingly, they reflect our Scope 1, Scope 2 and NCI targets over the next ten years. However, Shell’s operating plans cannot reflect our 2050 net-zero emissions target, as this target is currently outside our planning period. In the future, as society moves towards net-zero emissions, we expect Shell’s operating plans to reflect this movement. However, if society is not net zero in 2050, as of today, there would be significant risk that Shell may not meet this target.

Forward-looking non-GAAP measures

This story may contain certain forward-looking non-GAAP measures such as cash capital expenditure and divestments. We are unable to provide a reconciliation of these forward-looking non-GAAP measures to the most comparable GAAP financial measures because certain information needed to reconcile those non-GAAP measures to the most comparable GAAP financial measures is dependent on future events some of which are outside the control of Shell, such as oil and gas prices, interest rates and exchange rates. Moreover, estimating such GAAP measures with the required precision necessary to provide a meaningful reconciliation is extremely difficult and could not be accomplished without unreasonable effort. Non-GAAP measures in respect of future periods which cannot be reconciled to the most comparable GAAP financial measure are calculated in a manner which is consistent with the accounting policies applied in Shell plc’s consolidated financial statements.

The contents of websites referred to in this story do not form part of this story.

We may have used certain terms, such as resources, in this story that the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) strictly prohibits us from including in our filings with the SEC. Investors are urged to consider closely the disclosure in our Form 20-F, File No 1-32575, available on the SEC website www.sec.gov

Third life for the North Sea

9 Jan. 2026

For a long time, extracting natural gas from the North Sea seemed to be a winding down business. But since 20222, with the cuts in Russian gas flowing to Europe and spiking energy prices, the waters that connect the Netherlands, Belgium, the United Kingdom, Norway, Denmark, and Germany are back in the picture as a potential source of oil and gas.

Text: Rob van 't Wel, supplemented by Marcel Burger.

Infographic: Dirk Jan Pino. Photography: Shell plc., Stuart Conway, A/S Norske Shell.

Original publication: 30 Nov 2022. Updated and supplemented: 9 Jan 2026.

Search the internet with keywords “North Sea” and “offshore”, and depending from where you log in, there is big chance wind farms pop up. It is an illustration of the global energy transition we are in, and it tells the tale of the increased importance of wind as a sustainable energy source.

Things may change. For a long time, the extraction of oil and gas in the North Sea seemed to be an example of an industry that was doomed to extinction. The 'big boys' of the energy sector built up their activities in the North Sea and left the crumbs for the smaller players to get the last scraps.

As a result of the war in Ukraine, and its side effects, that image has been changing since 2022. The high energy prices welcome opportunities for new, profitable activities at sea. In addition, governments are looking to reduce dependence on unreliable suppliers. It is a common thread in the development of the North Sea as an oil and gas extraction area.

Suez crisis

The first wave of investments into the North Sea for fossil energy production comes in the autumn of 1956 during the Suez crisis. Although there are reasons why tensions were growing at the time, Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser's nationalization of the Suez Canal is the direct cause of armed conflict. As a result, oil exports from the Middle East to Europe are in jeopardy.

This dependence is the impetus for the search for alternatives and that is how the North Sea attracts attention. But who owns that potential wealth? Therefore, all oil activities begin with diplomatic talks. Two years after the Suez crisis, the so-called Convention on the Continental Shelf is concluded in Geneva. The agreement sets the limits for the division of the North Sea and thus the rights for exploration and production of fossil mineral resources.

A fierce hunt for oil and gas at sea is on in the 1960s, with the oil and gas discoveries on the surrounding mainland – including the Groningen field in the Netherlands in 1959 – as an extra incentive. But the results are moderate at best, which leads to a decrease in enthusiasm. Until December 1969, when the Ekofisk gas field is found in the Norwegian part of the North Sea, followed by a considerable oil field in Scottish waters.

Shell and the North Sea

Shell has a long tradition of offshore oil and gas extraction at the North Sea, in the Netherlands mainly through the joint venture NAM. Since 2019, Shell has been very active in offshore wind power in the Netherlands as well, with the fourth wind farm off the Dutch coast under construction at this moment.

Bonanza

The United Kingdom and Norway appear to be the main winners of the offshore bonanza. The major investments take place in their economic zones, but a period of uncertain oil supplies lies ahead: the energy crises of 1973 and 1979. Renewed tensions in the Middle East, and the Arab oil producers closing the tap, makes North Sea countries’ governments respond with new investment stimulations in their waters. In the Netherlands the so-called small fields policy is introduced in 1974. The most important element of it: there is always a buyer for produced North Sea gas. This certainty leads to a new wave of investments, because North Sea producers no longer have to compete with e.g. Groningen gas of which production costs are considerably lower.

As the first large North Sea fields reach the end of their production life, so do the glory days of offshore production in this part of the world. All easy-to-find fields have been tapped into, have passed their top production, while fossil fuels are under pressure and wind farms require space and new money. With Russia no longer considered an enemy of “the West” in the 1990s and beginning of 2000s, ever more competitive gas finds its way to Western Europe through deals made with Moscow. As a European energy “province” the North Sea is dying. Big players are increasingly selling their interests to smaller parties financed with venture capital.

Green light

It is early 2022 when yet another “world event” puts the North Sea back into focus. On 24 February, Russia launches a full-scale invasion of Ukraine – eight years after a slow and partly hybrid war in which Russia took the Crimea peninsula and parts of the Luhansk and Donetsk regions from Ukraine.

The dependence on Russia as energy supplier shows no mercy. Add energy embargoes and political wrangling and the price of energy hits record after record. Reason for countries to, once again, eye the North Sea and reduce their reliance on Moscow.

In April 2022, the Dutch cabinet announced its intention to facilitate gas production off the coast. Britain and Denmark follow within the week. It is very much welcomed by “the market”. Together with higher gas prices, the governments’ incentives make investments more secure and profitable.

Natural gas consumption and sources in the Netherlands

Of all the natural gas consumed in the Netherlands in 2024, 38% still came directly from Dutch fields. In addition, almost one third (27%) arrived as LNG from the United States. Norway supplied 14% of the gas the Netherlands required, while the rest of the EU accounted for a further 6%. Finally, 13% came from outside the EU, Norway and the US, and a further 2% originated from Russia.

Source: EBN

Shell announces Jackdaw

At the end of May 2022, Shell announces development of Jackdaw, 250 kilometres (155 miles) off the coast of Aberdeen. Once in production, this large gas field will account for 6% of the UK's gas demand.

“The North Sea can play an essential role in limiting our import dependence,” writes the Netherlands’ State Secretary for Mining Hans Vijlbrief in a letter to the House of Representatives in July 2022. His letter is meant to speed up the permitting processes, including the warning that “the energy transition is not arranged overnight”.

Cubic metres

Additional gas extraction at sea is more modern than before, even its transport requires less energy, lowering the overall CO2 emissions on the balance sheet. With speeded up processes in place, in 2022 the Dutch State Secretary for Mining believes the Dutch economic zone of the North Sea can provide in an extra 2 to 4 billion cubic metres of gas annually over the next five years, on top of the 8.9 billion cubic metres of 2021. Earlier, production growth was to be capped at 1 billion cubic metres of natural gas. Note: the annual gas consumption of the Netherlands is about 40 billion cubic metres.

Dutch gas declines further

But Dutch natural gas production continues to fall. In 2023 it is even 10% lower than expected, according to research by the renowned TNO institute. This applies to the so‑called “small fields”: all gas fields excluding the Groningen gas field. In April 2025 the Dutch government signs a Sector agreement on Gas Extraction in the Energy Transition in April 2025, with government-controlled Energy Management Authority of the Netherlands (EBN) and the industry association Element NL. Goal: to extract the remaining (potential) natural gas in the North Sea responsibly.

A youth with growing pains

The North Sea’s third youth comes with growing pains. After some delays—due to legal procedures—Jackdaw remains a new initiative for the British section of the North Sea. In Norway, Shell continues to be a stable and reliable gas supplier for Europe, as a partner in Troll and as operator of Ormen Lange – the largest gas fields on the Norwegian continental shelf.

In the Dutch section of the North Sea, 2024 saw, for the first time since 2002, almost sufficient offshore gas reserves being identified to compensate for 95% of the recent annual production decline, according to TNO. At the end of 2024, TNO estimates the total proven offshore natural gas reserves for the Netherlands at 40 billion cubic metres.

How "Viking gas" keeps flowing to the Netherlands

Today, Ormen Lange is Norway’s second‑largest offshore natural gas production project and makes a significant contribution to Europe’s energy security. And it is precisely at Ormen Lange that engineers have recently carried out an impressive feat of deep‑sea engineering to maintain production levels.

Cautionary note

Cautionary note

The companies in which Shell plc directly and indirectly owns investments are separate legal entities. In this story “Shell”, “Shell Group” and “Group” are sometimes used for convenience where references are made to Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general. Likewise, the words “we”, “us” and “our” are also used to refer to Shell plc and its subsidiaries in general or to those who work for them. These terms are also used where no useful purpose is served by identifying the particular entity or entities. ‘‘Subsidiaries’’, “Shell subsidiaries” and “Shell companies” as used in this announcement refer to entities over which Shell plc either directly or indirectly has control. The term “joint venture”, “joint operations”, “joint arrangements”, and “associates” may also be used to refer to a commercial arrangement in which Shell has a direct or indirect ownership interest with one or more parties. The term “Shell interest” is used for convenience to indicate the direct and/or indirect ownership interest held by Shell in an entity or unincorporated joint arrangement, after exclusion of all third-party interest.

Forward-looking Statements

This story contains forward-looking statements (within the meaning of the U.S. Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995) concerning the financial condition, results of operations and businesses of Shell. All statements other than statements of historical fact are, or may be deemed to be, forward-looking statements. Forward-looking statements are statements of future expectations that are based on management’s current expectations and assumptions and involve known and unknown risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results, performance or events to differ materially from those expressed or implied in these statements. Forward-looking statements include, among other things, statements concerning the potential exposure of Shell to market risks and statements expressing management’s expectations, beliefs, estimates, forecasts, projections and assumptions. These forward-looking statements are identified by their use of terms and phrases such as “aim”; “ambition”; ‘‘anticipate’’; ‘‘believe’’; “commit”; “commitment”; ‘‘could’’; ‘‘estimate’’; ‘‘expect’’; ‘‘goals’’; ‘‘intend’’; ‘‘may’’; “milestones”; ‘‘objectives’’; ‘‘outlook’’; ‘‘plan’’; ‘‘probably’’; ‘‘project’’; ‘‘risks’’; “schedule”; ‘‘seek’’; ‘‘should’’; ‘‘target’’; ‘‘will’’; “would” and similar terms and phrases. There are a number of factors that could affect the future operations of Shell and could cause those results to differ materially from those expressed in the forward-looking statements included in this story, including (without limitation): (a) price fluctuations in crude oil and natural gas; (b) changes in demand for Shell’s products; (c) currency fluctuations; (d) drilling and production results; (e) reserves estimates; (f) loss of market share and industry competition; (g) environmental and physical risks; (h) risks associated with the identification of suitable potential acquisition properties and targets, and successful negotiation and completion of such transactions; (i) the risk of doing business in developing countries and countries subject to international sanctions; (j) legislative, judicial, fiscal and regulatory developments including regulatory measures addressing climate change; (k) economic and financial market conditions in various countries and regions; (l) political risks, including the risks of expropriation and renegotiation of the terms of contracts with governmental entities, delays or advancements in the approval of projects and delays in the reimbursement for shared costs; (m) risks associated with the impact of pandemics, such as the COVID-19 (coronavirus) outbreak, regional conflicts, such as the Russia-Ukraine war, and a significant cybersecurity breach; and (n) changes in trading conditions. No assurance is provided that future dividend payments will match or exceed previous dividend payments. All forward-looking statements contained in this story are expressly qualified in their entirety by the cautionary statements contained or referred to in this section. Readers should not place undue reliance on forward-looking statements. Additional risk factors that may affect future results are contained in Shell plc’s Form 20-F for the year ended December 31, 2024 (available at www.shell.com/investors/news-and-filings/sec-filings.html and www.sec.gov). These risk factors also expressly qualify all forward-looking statements contained in this story and should be considered by the reader. Each forward-looking statement speaks only as of the date of this story, January 9, 2026. Neither Shell plc nor any of its subsidiaries undertake any obligation to publicly update or revise any forward-looking statement as a result of new information, future events or other information. In light of these risks, results could differ materially from those stated, implied or inferred from the forward-looking statements contained in this story.

Shell’s Net Carbon Intensity

Also, in this story we may refer to Shell’s “Net Carbon Intensity” (NCI), which includes Shell’s carbon emissions from the production of our energy products, our suppliers’ carbon emissions in supplying energy for that production and our customers’ carbon emissions associated with their use of the energy products we sell. Shell’s NCI also includes the emissions associated with the production and use of energy products produced by others which Shell purchases for resale. Shell only controls its own emissions. The use of the terms Shell’s “Net Carbon Intensity” or NCI are for convenience only and not intended to suggest these emissions are those of Shell plc or its subsidiaries.

Shell’s net-zero emissions target

Shell’s operating plan, outlook and budgets are forecasted for a ten-year period and are updated every year. They reflect the current economic environment and what we can reasonably expect to see over the next ten years. Accordingly, they reflect our Scope 1, Scope 2 and NCI targets over the next ten years. However, Shell’s operating plans cannot reflect our 2050 net-zero emissions target, as this target is currently outside our planning period. In the future, as society moves towards net-zero emissions, we expect Shell’s operating plans to reflect this movement. However, if society is not net zero in 2050, as of today, there would be significant risk that Shell may not meet this target.

Forward-looking non-GAAP measures

This story may contain certain forward-looking non-GAAP measures such as cash capital expenditure and divestments. We are unable to provide a reconciliation of these forward-looking non-GAAP measures to the most comparable GAAP financial measures because certain information needed to reconcile those non-GAAP measures to the most comparable GAAP financial measures is dependent on future events some of which are outside the control of Shell, such as oil and gas prices, interest rates and exchange rates. Moreover, estimating such GAAP measures with the required precision necessary to provide a meaningful reconciliation is extremely difficult and could not be accomplished without unreasonable effort. Non-GAAP measures in respect of future periods which cannot be reconciled to the most comparable GAAP financial measure are calculated in a manner which is consistent with the accounting policies applied in Shell plc’s consolidated financial statements.

The contents of websites referred to in this story do not form part of this story.

We may have used certain terms, such as resources, in this story that the United States Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) strictly prohibits us from including in our filings with the SEC. Investors are urged to consider closely the disclosure in our Form 20-F, File No 1-32575, available on the SEC website www.sec.gov